Le Royal Dressmaker

“A man should look as if he bought his clothes with intelligence,

put them on with care, then forgot about them.”

-Hardy Amies

Incorporated in 1946, The House of Hardy Amies is situated on London’s famous Savile Row, the true home of Bespoke clothing.

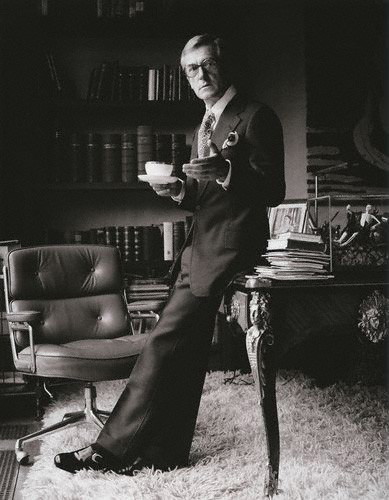

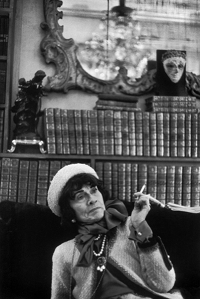

Amies was widely admired for his fine tailoring, attention to detail and upper crust style. Is there any doubt? Just look at him. He oozes class. Double breasted pin stripped suit, gelled hair, pocket handkerchief. The epitome of panache and polish! Not unsurprisingly, he started a men’s line in the 60’s. He was also the stylist for some wonderful films, including 2001 Space Odyssey and Two For the Road.

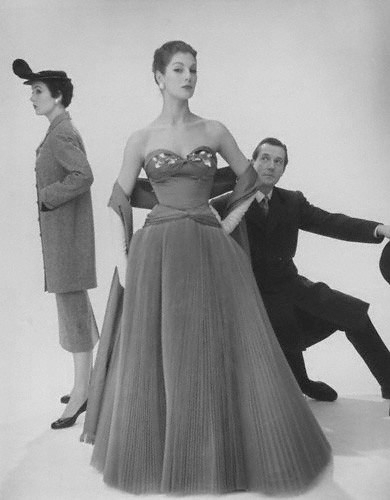

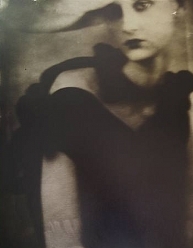

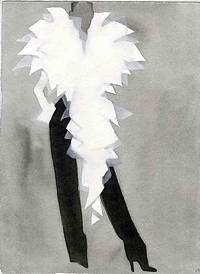

Aimes photographs one of his elegant evening gowns, UK, 1965

Hardy Amies is best known as the Royal Dressmaker to Queen Elizabeth. The Queen may never have been a fashion plate, but her quiet wardrobe reflected a spirit of aristocratic England that preferred clothes that would not “frighten the horses.”

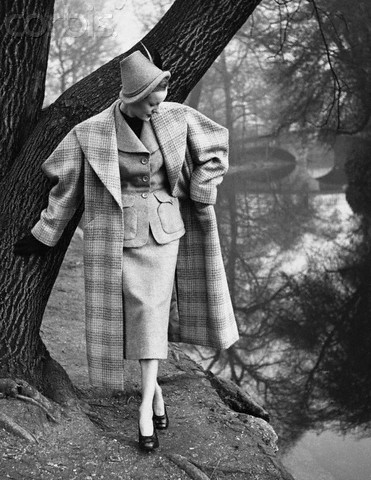

Design by Sir Hardy Amies, ca. 1951.

Known for his acid wit as well as for the creation of the vivid but simple and feminine royal style, Amies’ best known creation was the gown he designed in 1977 for Queen Elizabeth’s Silver Jubilee portrait which, he claimed, was “immortalized on a thousand biscuit tins.”

Barbara Goalen models Hardy Amies

Amies formed the last bastion of British couture, holding twice-yearly shows where a small but loyal and well-heeled clientele filed into his showroom to take their place on little gilt chairs and applaud womenswear that upheld the great British tradition of clothes that were beautifully made but rigorously conservative.

A model wears a fitted, Cumberland tweed, Amies’ suit with checked, wrap-around coat to match. UK, 1950.

A master of the bon mot, his favorite phrase was that “great style is insouciance — it is very vulgar to be impressed by your own clothes.”

Sir (Edwin) Hardy Amies with two fashion models.

Following the mandate that a woman of breeding would not be comfortable or, dare be viewed as, conspicuous parading about town – or country – dressed like the proverbial Christmas tree, Aimes rigidly held to promoting a look and style that many thought downright dowdy.

Sir (Edwin) Hardy Amies.

The most admired trait of Hardy Aimes might best be summed up in his declaration of being a self-proclaimed snob because, he said, it meant “liking what is best.”

Space didn’t allow for amplification, but Sir Hardy Amies was such a fascinating individual, I include the eulogy written upon his death in the Daily Telegraph in 2003.

Sir Hardy Amies, who died yesterday aged 93, founded the most internationally successful couture house in Britain and was, from the time of her accession, dressmaker to the Queen.

Amies established the monarch’s crisp, understated style of dress. “I don’t think she feels chic clothes are friendly,” he once told an interviewer. “The Queen’s attitude is that she must always dress for the occasion – usually for a large mob of middle-class people towards whom she wishes to seem friendly.”

He described his women’s clothes as “sporty, expensive-looking and lady-like”, adding, “Put the initials together and that’s what they do – sell.” He once claimed to design them mainly for the money, though he always insisted on the highest quality. A woman’s day clothes “must look equally good at Salisbury Station as the Ritz bar”, he said. “Our customer always has one foot in the country, one in the town.” Among his other pronouncements was, “Scarlet should be left to the Alpine Rescue Squad.” He was, though, much prouder of his men’s fashions, which he brought to the mass market in the 1960s.

Yet Amies, a Savile Row couturier for more than 50 years, remained a traditionalist: in a letter to The Daily Telegraph in 1993 he wrote, “It is clear that the man’s suit – an English invention, I must add – is still worn by men at all times when respect for tradition and hope for an ordered future prevail . . . The suit is the uniform of the gentleman.”

He attributed his popularity overseas to the distinctively English elegance and nonchalance of his clothes, and rather enjoyed the indifferent attitude of his fellow countrymen to sartorial matters. “Even though it defeats me as a dressmaker, I admire the British attitude,” he once said. “Clothes are not really as important as all that.”

Edwin Hardy Amies was born at Maida Vale on July 17 1909; his father was an architect for the London County Council and his mother a vendeuse for a Court dressmaker in Bond Street. Young Hardy was educated at Latymer Upper School and Brentwood.

It was suggested that he should work for a scholarship to Cambridge, but Amies wanted to become a journalist. His father arranged for a meeting with R D Blumenfeld, the editor of the Daily Express, who told him: “We don’t want academics in the journalistic world. We want men of international culture. Send him abroad to learn French and German. Make him work.”

After spending three years in France and Germany – learning the languages and working for a customs agent, an English school and a wall-tile factory – Amies returned to England and became a weighing-machine salesman for W & T Avery.

It was Amies’s facility with the written word that secured him his first job in fashion. His vivid description of a dress, written in a letter to a retired French fitter and brought to the attention of the owner of the Mayfair couture house Lachasse, made a strong impression. The wearer of the dress was the owner’s wife.

In early 1934, with no previous experience, he succeeded the designer manager, Digby Morton, who had left Lachasse to set up his own house. Amies later said that many of his early designs were both hideous and extravagant, but in 1937 he scored a success with a tweed suit called “Panic”. By the time war intervened, he was designing the whole collection.

During the Second World War, Amies joined the Belgian section of SOE as second-in-command to Lt-Col Claude Knight, whom he later succeeded in command. Working with the various Belgian Resistance groups, he organised sabotage and arranged for agents to be parachuted with radio equipment into the Ardennes. In his spare time, he slightly redesigned his lieutenant-colonel’s uniform and had it made up by a civilian tailor.

On demobilisation, Amies bought the lease of a house in Savile Row, built by Lord Burlington in 1735 and damaged in the Blitz, and set up his own business.

He determined in the 1940s to get rid of his “suburban gaucherie” and learn the “lingo” and manners of the upper classes. He was, and remained, a self-proclaimed snob – indeed the snobbism was part of his charm: “I’m for elitism and its survival,” he explained. “There’s nothing wrong with it; it’s usually benevolent and has good effects.” At the same time, he was always the first to acknowledge his modest birth: “Not bad” he would say of his success, “for a suburban frock-maker.”

It was not long before he was designing clothes for Princess Elizabeth. “A very grand lady asked me to make coats and skirts for what she called her ‘gels’ “, he recalled, “and they turned out to be ladies-in-waiting to Princess Elizabeth. The Princess saw them and asked me to make clothes for her visit to Canada in 1948.” His royal warrant dated from her accession to the throne.

The Queen could not wear dark colours, he explained, because she would look in photographs as if she were in mourning; she chose not to wear beige because she thought people might not recognise her.

The Queen wore a Hardy Amies pink silk dress and coat for the Silver Jubilee and a Hardy Amies yellow coat on her 60th birthday. Less successful was the highly frilled and puffed Hardy Amies cream ballgown she wore to a state banquet held by the Reagans in 1983: the bows on its shoulders clashed with her spectacles.

In 1950, recognising a need for cheaper, instantly available clothes, Amies expanded his business by opening a ready-to-wear boutique, which now accounts for 50 per cent of the Savile Row trade.

In the late 1950s he designed his first man’s shirt, and went on to become a consultant to Byfords (on socks and knitwear); Tootal (shirts, dressing gowns and pyjamas); Clarks (elastic-sided shoes); and Battersby Woodrow (soft felt hats). When he joined Hepworth’s as a consultant, designing an annual collection worth £10 million, he declared that “my mission in life is to create a wardrobe for what I call the ‘complete man’ “; he and Hepworth’s led the way in getting men’s fashion accepted by the mass market.

Amies described himself as being realistic rather than romantic about fashion. “I am flattered that few of my garments are found in museums. They have all been worn out.” He designed uniforms for the police, British Airways, the South African defence force, male nurses at Broadmoor and the staffs of W H Smith, the London Hilton and Wall’s ice-cream.

Amies’s new uniform for policemen in 1969 – a hacking jacket, slip-on shoes and narrow trousers – met with approval in the Force, but his designs were not always welcomed by British Airways’ stewardesses: a 1967 outfit was scrapped because it was thought “frumpish”.

In 1973 Amies sold his business to Debenhams, with a view to further expansion, but in 1980 bought it back with the profits of his success with menswear in Canada, Australia, Japan, America and New Zealand (where, he estimated in 1979, 55 per cent of men wore suits in whose design he had a hand). Eventually, he had more than 40 overseas licensees.

Amies had a waspish wit and his bon mots were eagerly awaited. “How scruffy you look today, dear boy,” he might tell a young assistant: “I can’t imagine what your underwear looks like.” His rivals generally earned his sharpest gibes. “What are you wearing?” he asked one unfortunate journalist; “Armani, I suppose? Genitalia fastening! You can’t have buttons below the waist.”

Handsome, with aquiline features and a full head of hair, Amies was proud of his athletic figure and played tennis well into his eighties. His other principal love was gardening, and he built from scratch an elaborate traditional country garden at his home in Oxfordshire, a converted school house. He also enjoyed needlepoint, gros and petit point (though he never learned to sew), and had a passion for pictures of Stuart monarchs.

Amies never denied his homosexuality, though he did not flaunt it. He lived quietly with one man for 22 years but, when he went out socially, the lover remained at home: “It’s just too common for two men to go around together,” he explained. He was, though, proud of the fact that he never lost his eye for youth and beauty.

Amies was Chairman of the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers from 1959 to 1969. For a short period in the early 1990s he wrote a fashion column for Esquire magazine. He also published his autobiography in 1984, which even then was called Still Here. Looking back on his life, he concluded that one of the great advantages of modern life was that, with more bidets around, “my century has a cleaner bottom”. His epitaph, he suggested, should read “He was a court dressmaker and an elitist with a sense of humour.”

Hardy Amies was appointed CVO in 1977 and KCVO in 1989, by which time he had handed over the running of the couture house to Ken Fleetwood, his co-director in charge of design.

In 2000, Amies sold the house to the Luxury Brands Group and announced his formal retirement, although he hung up his scissors for good only last autumn.

A FINAL COMMENT: According to another obituary, Amies remained impeccably dressed throughout his life, although bent double in his later years by crippling arthritis of the spine. “But I can always straighten up to walk into the Ritz,” he would say.

I’m not sure where to begin…

The first photo is perfection. The last one of him shows how one may be modern in dress, if one is vigilant about certain conventions. To wit: proportion, tailoring, understatement and giving a damn.

This was a treat, thank you.

E,

My humble thanks. To my mind, the real treat here was Amies’ colorful and perfectly composed life. How can one not be elevated by style, wit, intelligence, class and propriety. And the bons mots – priceless!

[…] From The Errant Aesthete. There are tidbits of elegance scattered about this post like so many dark chocolates, waiting to be ingested, exclaimed upon and savoured. […]

Glamourous. Eccentric. Witty and perfectly executed.

I also love Lily Allen —-

pve

pve design,

I’m a huge fan. Thank you for your very kind words.

what a wonderful post !

i am a horse woman myself, and nothing would say more than let’s not “frighten the horses.”

The Queen seemed to have had definite ideas on how others viewed her wardrobe.

Beautiful & witty, thank you! I have had his “ABC of Men’s Fashion” on my shelf for a while, but did not know much about the man himself..

[…] Read the original post: Le Royal Dressmaker « The Errant Æsthete […]

Le Royal Dressmaker « The Errant Æsthete | MaleOutfit.Com said this on 02/27/09 at 12:02:52 |

Fascinating posting — many many thanks for such wonderful history — and photographs! Oddly enough — I was reminded of Fred Astaire when I looked at Mr. Amies — both have long, lean elegant lines of grace in their stance. Never studied — simply innate as if the movement was so much part of their basic nature. I do hope that thought makes some sense! Off to put the kettle on — I am in sore need of darjeeling! Kindest regards, Jan at Rosemary Cottage

No mention of Hardy’s work in WW2, helping potential secret agents identify their enemy by careful study of their uniforms. He was always considered impeccably dressed by his ‘students’. His uniform was made on Saville Row. Later he was transferred to Norgeby House, London, to run the Special Operations Executive’s Belgium Section.

Any chance I can use his photo in a potential book on the three women he sent into Belgium on TOP SECRET missions. They weren’t attired in haute couture tho…

Bernard O’Connor

Thank you for that most welcome addition. Perhaps something for a future post. I would love to hear more. Sounds like a fascinating topic.

As to the photographic choices, all were culled from the prodigious Internet. For inclusion in a publication, you best check with the bearer of said rights for the individual photo you’re interested in using. It may take some doing to track down the source since imaging exchange is hardly regulated or enforced. I would think an estate oversees the use of likenesses, etc. Then, again, it may prove to be

public domain, which gives you complete freedom. Best of luck in your endeavors.

[…] Le Royal Dressmaker « The Errant Æsthete via theerrantaesthete.com […]

Le Royal Dressmaker « The Errant Æsthete « [art talk] said this on 06/10/10 at 09:06:24 |

Lovely site – and wonderful sentiments about a remarkable person – but to me he was just Uncle Hardy.

[…] photoby Patrick Lichfield (Thomas Patrick John Anson, 5th Earl of Lichfield),photograph,August 1970 Source He did not talk directly to me – you could feel the cold annoyance permeating from him […]

Things I have learned in the past three days- Amies (Hardy) – Amie « That Woman’s Weblog said this on 01/20/12 at 08:01:27 |